Prologue

Uncle Boon Reminisces - Mahbob Abdullah December 2003

|

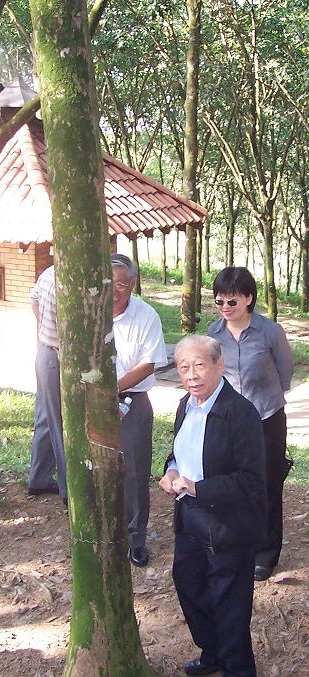

Mr. Boon Weng Siew, known to many planters as ‘Uncle Boon’, who, not so much for his age, but for his avuncular way of dealing with others, was frank, straightforward and never had a harsh word.

He reminisces …

“I was born into plantation life,” he said, “my father was a tapping contractor on Gading Estate at that time in 1923. But it was in Tebolang Estate where I grew up, and I saw as a child how an estate worked, and how powerful the British (Mat Salleh) Estate Managers were. There was a Manager called Rex Duncan who was kind to me. He had come to Malaya a few years before and I learnt about estate work there. He was tall and slim and I think he followed my progress in school. My father had wanted me to be a planter; so he sent me to the Tampin Government English School after my primary education in Chinese, and then to St. Paul’s Institution in Seremban. But then the war came. It was a turning point for my studies. I returned to Tebong when the buildings of St. Paul’s became barracks for British soldiers, who arrived in mid-1941 to defend Malaya against the Japanese invasion. In Tebong, I joined the Local Defense Corps (LDC) with Rex Duncan in command. I got a few months of military training.

“The Japanese invaded Malaya on 8th December, 1941. I remember that when the bombs started to drop at the Tebong railway station, I was there among scores of British soldiers. I was the LDC dispatch driver then. I got out, but a couple of British soldiers were killed, and many more were hurt. The bombs hit a row of shop-houses too, but luckily our two houses were spared.

“When Rex Duncan prepared to retreat to Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), he had asked me to go with him for military training there and to return as a member of Force 136. I was only 19 but was already in love with a girl called Piong Kim Lan. She was the eldest daughter of a retired estate contractor, who owned a rubber plantation in Ayer Kuning South, 10 miles from Tebong. Love and war. Uncertain times. I did not know what was going to be my life span then. It could have been a turning point in my life. But I did not go, and got married instead. I did my part in the war in another way. But it turned out in the end I joined Force 136 anyhow.

“It came about in an indirect way. In April, 1945, while I was working in Sagil Estate, I was asked by the North Johor Command of the Malayan People’s Anti Japanese Army (MPAJA) to join them as interpreter for Force 136 liaison officers who had just been air-dropped in the jungle between Jementah and Pagoh. I stayed in the jungle for about four months, until the Japanese surrender in August, 1945. Life was tough in the forest but become more bearable when we got food supplies airdropped from Colombo, which included canned meat, sardine, powdered milk, butter and cheese all of which were not available in towns.

“The first officer to arrive in Malaya from Force 136 was Colonel Lim Bo Seng. A submarine brought him near Pangkor Island, where Chin Peng of the Malaysian Communist Party (MCP) met him. It was the beginning of the cooperation between Force 136 and the MPAJA. Later two British officers joined them, Major John Davis and Captain Richard Broome. They set up a radio link with the British South East Asia Command in Colombo. Another officer became famous later on. He was Captain Spencer Chapman, who stayed behind when the British army retreated to Colombo in l942. He trained MPAJA members on guerilla warfare, and created arms and supply dumps behind Japanese lines. He wrote the book “The Jungle Is Neutral.”

“I did not meet him. But I met the head of the communists - Chin Peng once, in 1947, at the Malayan Communist Party office in Queen’s Street in Singapore. He was the new Secretary General of the MCP then, and he was only 23. A year younger than me. He is still alive, and he wrote a book too, which came out recently, giving his side of the story. But Colonel Lim Bo Seng was caught by the Japanese in 1944. He was killed in Batu Gajah prison. A monument was erected in Singapore to honour his memory; it is still there at the Esplanade.”

“The war ended in August, 1945, after two atomic bombs were dropped in Japan. I thought that peace had come at last. But the following few weeks were just as bad”.

“Though the Emperor had called on all the Japanese soldiers to give up, many places did not get the orders or did not believe the war was lost. The killings went on. They would not surrender to Force 136 either, and waited for the regular British army to arrive. For a few weeks, I remember, the MPAJA assumed the role of rulers. Many old scores were settled. When the British returned, MPAJA was disbanded. The British awarded medals to members of MPAJA, including members of Force 136, of which I was treated as one.”

“I stayed in Johor Bahru for a while. Soon, like many idealistic young men, I followed some of the leaders of the disbanded MPAJA to Singapore. It was the political, economic and educational nerve centre. There I got to meet John Eber, Lim Hong Bee, Lim Kean Chye, Gerald De-Cruz and P.C. Quok of the Malayan Democratic Union. “

“I soon became the Executive Secretary of the Singapore Seamen’s Union, and met regularly with other active Union Leaders. One of them was Mr. Lim Yew Hock. He was General Secretary of the Singapore Clerical and Administrative Workers’ Union. Devan Nair was another. He was Secretary of the Singapore Teachers’ Union while P. V. Sharma was its President. That was also the time when I got to meet Nehru, and interpreted for him when he spoke at a mass rally in “Little India” when he visited Singapore in 1947.

“I learnt a lot from the people I met, particularly those in the Malayan Democratic Union who were all intellectuals, and in some ways it was an education by itself, taking the place of University life that I did not get. But that period had to end. When the state of emergency was declared in 1948, I had to leave Singapore and returned to Malacca to take up the post of Executive Secretary of both the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malacca Chinese Chamber of Commerce. Subsequently I became the personal assistant to the late Tun Tan Siew Sin, who was then Managing Director of Unitac, Ltd. a plantation management agency. He was also the Hon. Secretary of MCA and his father, Tun Tan Cheng Lock, the President.”

“Tun Tan Siew Sin was such a fine man that I stayed on with him for a long time. And of course I learnt a lot from him, not only on politics, but also on life. He was serious, but he had a sense of humour too, in the way he would teach me a thing or two. I liked to drive fast in those days, and once when I was driving him to an estate, I was in a hurry when he turned to me and said, “Boon, listen to me. It is better to arrive twenty minutes late, than to arrive twenty years earlier.” I will never forget that!”

“But that job of a personal assistant to him had to end when he appointed me Manager of Melaka Pinda Estate in 1953. That was how I got into plantations again. Just another turning point if you like, but a definite one, for I stayed with the plantation industry ever since. In a way it was fulfilling what my father had hoped I would do.”

“Plantations were not always as easy as we know it now. My father had told me that during the rubber slump in the 1920s, due to the drastic fall in price after the end of World War I, the Stevenson Restriction Scheme (SRS) was introduced. It put a lid on production, which meant, of course, there was no more rubber tapping contracts for my father. He had to switch to other things. He opened a grocery shop for a time in Tebong. The rubber crisis did not stop rubber planting, though, and he soon got a contract to plant rubber in Tebolang Estate. I can recall the figures now. The rubber planted area in Malaya was 779,000 acres in 1920, and it nearly doubled by 1932. The controversial SRS ended in 1928. There was a bright side to it because the crisis spawned some new ideas - the Rubber Research Institute was one, and so was the School of Agriculture at Serdang, which is now a University. Then the Asiatic Planter’s Association was formed, which we later called the United Planting Association of Malaysia (UPAM) and which we now know as the MEOA (Malaysian Estate Owners’ Association).”

“My father had taught me a lot about plantation work, and I remember him fondly. But it was sad how he died. He was head of the Chinese community at Tebong, and because he helped raise the China Relief Fund, the Japanese tortured him in front of my mother, me and other members of the family. That was in 1942. He passed away in 1946 as a result of his injuries.”

“My planting days were mainly in Johor in the Malay Peninsula. During the Japanese occupation, I worked in Sagil Estate. The manager was a chemist called Sukumaran Menon. The Japanese wanted us to grow more food. Rubber production was limited to meeting their need only. I remember Mr. Menon clearly, because he could turn rubber into petroleum by distillation, and used it to run the estate’s vehicles. On the other hand, in the USA, the Americans were turning petroleum into synthetic rubber, as they could not get any rubber from here. Both rubber and petroleum are hydrocarbons, of course.”

“Even when I was in Melaka from 1953 to 1965, I spent a lot of time in visiting estates in Johor. Finally I moved to Johor in 1965 to take up the management of Mount Austin Estate, and at the same time served as Executive Director of Kemayan Oil Palm Berhad. Based at Johor Bahru, I made regular visits to plantations owned by Kemayan Oil Palm Berhad in Pahang and Sabah. This was possible because the controlling shareholders of Mount Austin Estate were also the dominant shareholders of Kemayan though they two were separate entities.”

“Unlike today, rubber was the main plantation crop in the 1960s. Oil Palm only started becoming dominant from the mid 1970’s when Tun Abdul Razak pushed for it via the FELDA schemes when he became the second prime minister. We were always learning something new. I presented a paper at a Rubber Research Institute conference in the 1960’s on the effect of mechanized ground preparation for replanting on root diseased areas. It could clear some doubts about mechanization. It was published in the RRIM Planters’ Bulletin.”

“But one of my big disappointments was the failure of the Malaysian cocoa industry, which went down as fast as it went up. The area fell from 393,465 hectares in 1990 to 65,000 hectares in 2002. One problem was the cocoa pod borer that messed up the beans. When the prices fell, it was a double blow.”

“There were happy moments too. It was good when I could solve some industry issues. When Tun Ghafar Baba was Deputy Prime Minister in 1988, he gave his time to listen to us in United Planters Assoc of Malaya, UPAM (now known as M’sian Estate Owners Assoc – MEOA), as we wanted the legalization of Indonesian workers who were illegally employed in the estates – by now mainly oil palm estates. We just did not have enough Malaysians, as many left for jobs in towns, or settled in Felda. I was the President of UPAM then. Tun Ghafar agreed, and legalization began in early 1989.”

“But labour shortage is still with us in 2003. I wish the government would have a consistent national labour policy, so we do not have such problems. Sometimes ad hoc measures were taken, for example when foreign workers get into fights. It has disrupted recruitment. At the same time the existing workers had to leave at the end of their work permits. So the estates would lose crop, and our country suffers as well.”

“After all, agriculture is still important no matter what others may say. And it can be a stable base when other industries can be rocked by external forces. You remember how the oil palm had stood up during the 1997 currency crisis … the planting industry was our second largest export revenue earner then. World palm oil prices went up. At home we subsidized the price of cooking oil. The growers and smallholders enjoyed the high palm oil prices and kept up spending, which has helped us to prevent excessive deflation.”

“Now because palm oil prices are high again, profits are up, and some of us might lose sight of the issues. There are a few things I would say that we should not forget.”

“We must regard the present high prices as an opportunity to raise productivity by addressing deficiencies, if any, in areas such as soil and moisture conservation in conjunction with correct fertilizer usage and application dosage. Our unit costs must go down to a sustainable level at times of low price. We should rely more on mechanization and less on labour. We should also improve on environment and food safety, which are subject to global pressure.”

“We need to do more on tissue culture to raise oil yield per hectare. Already some plantations have planted hundreds of hectares with tissue culture clonal materials, such as those developed by Dr. Ng Swee Kee, which are achieving yields more than double the national average of 3.6 tonnes CPO per hectare in 2002. The vision of 8.8 tonnes per hectare by 2020 is possible, but we have to work a lot harder to reach that target set by our Minister, Datuk Seri Dr. Lim Keng Yaik. I think this can be done if we invest in correcting what is deficient today. We must not cut corners by saving costs at the expense of productivity.”

“But we also must take proactive control of our commodity sector. It is about our nation’s economic survival – no, about a war – a commodity war that we are in. Not much different if you think about it, from the fight for independence.”

“Looking back to the many turning points in the past 80 years of my life, I think, the most important and significant one was my swift departure from Singapore as soon as the state of emergency was declared - failing which I might have met the same fate as some of my friends, who perished in the jungle in their struggle for independence - and I might not have been able to celebrate my 80th birthday! That turning point had awakened me from an idealistic dream, and I settled down at last to serve the planting industry. I have done that for 50 years, for which I have no regrets.”

“I think I have had a good run both in my work and at home. Kim Lan and I are happily married. We celebrated our golden jubilee on 15th February 1992, together with our 6 daughters, only son and 9 grandchildren. Since then, we have been blessed with two great grandchildren.”

“On looking back, perhaps I have not done anything great. But I am happy to have evolved from a proletariat to a petty bourgeois – no small change in mindset! At my age, I can say what I want to say as well. I believe in parliamentary democracy and a national economic policy that is diversified, with a strong agricultural base so it can withstand any downturn.”

God bless Malaysia in its fight to survive and prosper. But it will no more be my fight – my role will soon come to an end.